Third Level Assessment – Aquatic and Riparian Habitat Assessment

Wildlife

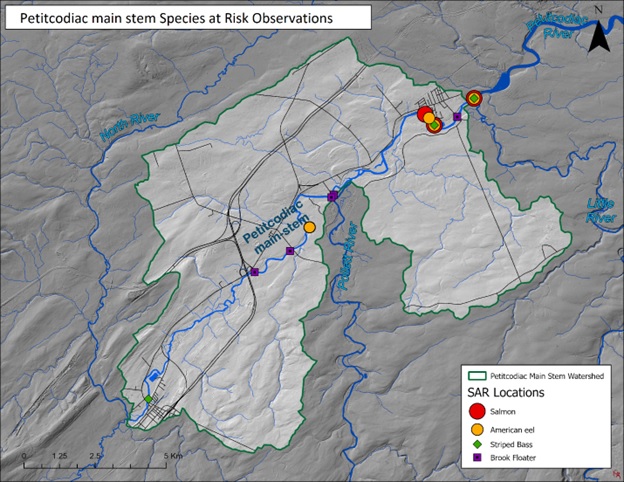

Several species of wildlife that warrant specific attention are found along the main stem of the Petitcodiac River watershed: Atlantic salmon, American eels, striped bass, brook floaters, and wood turtles. Guidelines for projects in areas with these are in the Appendix .

Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) Inner Bay of Fundy (iBoF) populations were listed as endangered under the Species at Risk Act in 2003 (DFO 2010; SARA Registry 2013a), and the species is considered extirpated from the Petitcodiac River system, except for those introduced in stocking programs (AMEC 2005). The decline in iBoF salmon is a marked contrast to the abundance described by early settlers (Dunfield 1991). Though numbers had been decreasing for some time (Elson 1962) construction of the causeway between Moncton and Riverview in 1968 complicated fish passage and extirpated the species from a river system that despite being one of 50 iBoF rivers, represented 20% of the total iBoF population (Locke, et al. 2003). Fort Folly Habitat Recovery encounters salmon (Figure 11) on the main stem of the Petitcodiac at the fish net trap (FNT) it operates at the head-of-tide in Salisbury. Modern encounters with salmon are effectively all due to recovery efforts, particularly ongoing stocking programs from both DFO’s Live Gene Bank at Mactaquac, and from Fundy Salmon Recovery’s sea pens on Grand Manan.

Completion of the Honorable Brenda Robertson Bridge (Figure 10) between Moncton and Riverview in 2021 strongly advanced salmon recovery efforts in the Petitcodiac. That fall, the first wild returning adult (photos and details) was captured at the FNT. This trap has been operated at two locations each shown on Figure 11 as the sites where Atlantic salmon, American eels, and striped bass have each been encountered. The original trap site, on the main stem just below the mouth of Little River operated from 2010 to 2017. The current trap site is about 2 km further upstream in Salisbury near Highland Park and has operated from 2018 to 2023.

The returning wild adult captured on October 4th, 2021, was distinctive because she lacked both a PIT tag and a floy tag. She showed no scars from having shed either type of tag, nor did it look as though a tissue sample had been taken from her caudal fin. In short, there was no sign that she had been previously handled. Scale and tissue samples were collected to allow further investigation. Stable Isotope Analysis carried out by the Stable Isotopes in Nature Laboratory (SINLAB) at the University of New Brunswick (UNB) confirmed that she was indeed a returning wild iBoF Atlantic salmon (Samways personal communication 2021), never handled by FFHR prior to her capture.

Examination of the scale sample indicated that she was a 2-sea-winter (2SW) fish, who had smoltified and gone to sea in 2019 as a two-year old smolt. As such, she would have been at sea in both December 2019 and December 2020. Having been captured on the main stem of the Petitcodiac beyond the mouth of the Little River, it seems reasonable to speculate that she was on her way upstream back to the Pollett River. Based on that, it is likely that she exited the Pollett as part of the Spring 2019 smolt run. FFHR’s 2019 data indicates a Bayesian Pollett smolt run size estimate of approximately 5,465 smolt. The tissue sample has been used for genetic analysis, but the results are not yet available. These may shed light on what part of the Recovery program she resulted from. One way or another, most smolt coming off the Pollett are present due to FFHR’s stocking efforts. Having been a two-year old smolt in 2019, she was probably either the offspring of the 126 Fundy Salmon Recovery adults released in October 2016 or one of 47,000 fry (directly sourced from the DFO Live Gene Bank at Mactaquac) released in May 2017. If she wasn’t released as a fry in Spring 2017 then one if not both of her parents were presumably among the adults released in the Fall 2016.

She is probably not alone – the FNT merely samples what is in the river. Catching one indicates that numbers have reached a level where the trap can detect them. It is premature to attribute detection of the returning wild salmon in 2021 entirely to the new channel under the bridge. That said, however, she must have passed under the bridge, and the improved passage it provides can only have helped her to do so. No additional returning wild adults were caught during either of the subsequent two years, though tagged adults have been detected by automated readers FFHR operates in both the Little River and the Pollett. The lack of another wild adult at the trap during 2022 and 2023 was noteworthy, and though somewhat disappointing, not particularly surprising. It does not mean that the individual caught in 2021 was a fluke, but merely highlights the fact that catching the first wild return was an unusual event. Two things can be simultaneously true: i.e. the odds of catching a returning wild adult salmon have increased as a result of ongoing iBoF Atlantic salmon recovery efforts, and that such fish remain uncommon enough doing so is unlikely.

A second significant salmon observation occurred in 2023 at the FNT, when 9 precocious parr (Figure 12) were encountered over a three-week period in late September and early October seeking out returning adults to mate with (Redfield 2024). During the previous 5 years at the current trap site, only 1 precocious parr had been seen. Such parr are an important reproductive component of the salmon population, since in years when few males return to spawn, precocious parr help ensure the fertilization of as many eggs as possible (Montgomery 1983). It has been suggested that proportions of mature male parr increase within Atlantic salmon populations (such as IBoF) that are experiencing high mortality at sea (Gibson 1978; Montgomery 1983), as genotypes that become sexually mature in freshwater avoid mortality at sea prior to reproduction (Caswell et al. 1984). However, Myers et al. (1986) concluded that it is more likely that observed changes in rates of maturation could be explained by density dependent factors influencing growth and development, rather than by actual shifts in gene frequency in response to selective pressure.

Myers et al. (1986) report once a fork length of approximately 13 to 14 cm is developed, virtually 100% of male parr remaining in rivers are sexually mature. Precocious parr often appear fat, as 20% of their body weight is comprised of testes (Montgomery 1983). The precocious parr in Figure 12 was one of two caught at the FNT on October 16th, 2023, in the company of an adult female who had been released just a few days earlier upstream on the Pollett. Precocious parr are attracted by hormones that adult females excrete in their urine (Olsén et al. 2002). The 7 precocious parr detected at the FNT in 2023 before these 2 were caught prior to October releases of FSR adults on October 13th. Consequently, those individuals were clearly searching for adults independent of 2023 releases. It seems possible they were doing so in response to movement of other adults – perhaps returns from 2022, or wild adult returns. The Pit Tag Antenna on the Pollett had already detected 10 returns of salmon released in 2022 by that time.

Regardless, what this indicates is that the population of juvenile salmon within the Petitcodiac are now actively participating during the spawning season. Salmon were extirpated from the Petitcodiac. For recovery efforts to have progressed to the point now where salmon within the river have developed the capacity to respond collectively to returning adults as a stressed population would, rather than FSR adults just being released into an empty river, is measurable progress.

American eels (Anguilla rostrata) were designated as “Special Concern” by COSEWIC in 2006 (COSEWIC 2006). Their status was re-examined and raised to “Threatened” in May 2012 (COSEWIC 2014a). This species is being considered for listing under the federal Species at Risk Act, but currently it has no status (SARA Registry 2013b). Similarly, American eels are frequently encountered by Fort Folly Habitat Recovery along the main stem. Eels demonstrate significant mobility within the system. In 2016 and 2017 eels tagged while coming downstream on the Little and the Pollett during the spring to feed in the estuary were later recaptured in the FNT (Figure 13) on the main stem coming back upstream in the late summer and fall to overwinter in freshwater. Unlike salmon, eels were not excluded by the Petitcodiac Causeway downstream. In fact, while the causeway gates were closed eels were found to be the most abundant resident species upstream of the headpond (Flanagan 2001), and one of the dominant species within the headpond (Locke et al 2000). Unfortunately the current trap site (2018 to 2023) does not provide as effective a means of monitoring eels as the original trap site had (2010 to 2017), and as a consequence electrofishing in the headwaters now provides the most effective means of tracking this species.

Striped bass (Morone saxatilis) within the Bay of Fundy were designated as “Endangered” by COSEWIC in 2012 (COSEWIC 2014b). This species is being considered for listing under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA), but currently it has no status (SARA Registry 2018). Striped bass were excluded from the freshwater reaches of the Petitcodiac while the causeway gates were closed (Locke et al. 2003) but have been making a rapid recovery since the gates were opened in 2010 (Redfield 2024), both in terms of numbers of young-of-the-year and adults (Figure 14).

For the first time in 2018 numerous large adults were detected on multiple occasions between August and October in a pool a short distance above the confluence of the Pollett with the main stem of the Petitcodiac, during snorkle surveys for salmon. Prior to 2018 the highest in the system this species had been observed since the gates were opened was the head of tide, however this observation shifted the highest point they’d been 7.5 km further upstream, most of it along the main stem, well above Salisbury. Since then, in 2021, striped bass have been caught by anglers at the railway bridge in the Village of Petitcodiac- at the very top of the main stem, not far below the point where the North River and the Anagance come together and become the Petitcodiac. It is thought that these individuals get so far up in the system while pursuing spawning gaspereau in May and June, as numerous similarly sized striped bass tend to be caught in the FNT at the head-of-tide during that time. It is notable however that the threshold at which striped bass becomes legal for anglers to keep on the Petitcodiac is 68 cm. While striped bass that big are caught with some regularity in the estuary at Dorchester or Belliveau Village, striped bass that big are yet to be seen at the FNT in Salisbury.

Brook floaters (Alasmidonta varicosa), are a medium sized (Figure 13) species of freshwater mussel listed as Special Concern by COSEWIC (COSEWIC 2009), and as Schedule 1, Special Concern, under the Species at Risk Act in 2013 (DFO 2016).

Brook floaters were well documented along the main stem by DFO in the late 1990s (Hanson and Locke 2001). Their numbers appear to have declined since that time due to a contraction in their habitat in response to silt brought upstream due to increases in tidal amplitude since the opening of the Petitcodiac Causeway gates (Redfield 2019). Of the 7 sites along the main stem of the Petitcodiac at which Hanson and Locke (2001) found brook floaters in 1997-1998 an FFHR survey twenty years later in 2018 detected brook floaters at only 4.

Overall, the decline in numbers of brook floaters appears to be a consequence of cumulative impacts from human activities – eutrophication, channel instability, and contraction of brook floater habitat as the head of tide shifted back upstream in response to the opening of the Petitcodiac Causeway gates. This was perhaps an unanticipated consequence of the restoration of tidal free tidal exchange in 2010. Brook floaters may have actually benefited from the causeway, due to the artificial increase in freshwater habitat near the mouth of Little River and are now losing that habitat as more estuarine conditions reassert themselves.

Wood turtles (Glyptemys insculpta) were designated as “Special Concern” by COSEWIC in 1996 which was raised to “Threatened” in 2007 (COSEWIC 2007; COSEWIC 2011). This species is listed as “threatened” under the Species at Risk Act (SARA Registry 2012). Wood turtles have been encountered at several locations along the main stem while conducting other field work. Due to their small home range, and vulnerability to poaching, encounters with wood turtles are considered to be sensitive information, and so are being withheld here. It is worth noting that the individual shown in Figure 16 is quite small- a juvenile. Adults are typically several times larger and have been seen as well on the main stem.