First Level Assessment-

Land use History of the Pollett River Watershed

Historical Background

Background

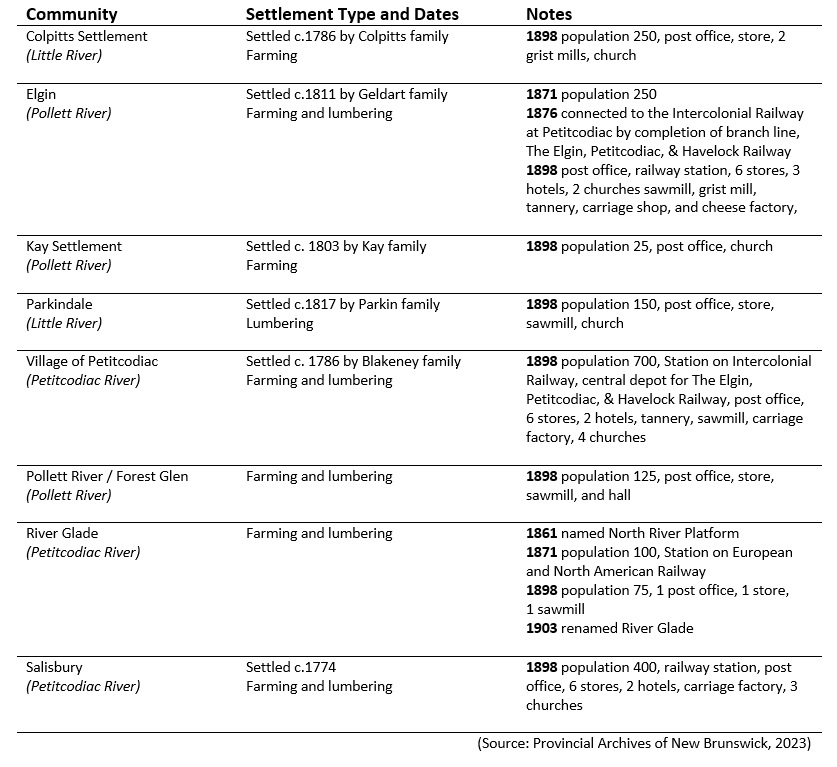

An understanding of the historical land use within a watershed provides context that helps explain the causes of issues affecting the watershed today. The following sections outline the historical land use both within the Pollett River watershed, and in the surrounding communities in both Westmorland County and Albert County. Within the Pollett watershed this includes the communities of Elgin, Pollett River (or Forest Glen), and Kay Settlement. Neighboring communities outside the watershed include: the village of Petitcodiac to the west; the village of Salisbury downstream a short distance below the confluence of the Pollett and the Petitcodiac River; and the communities of Colpitts Settlement, and Parkindale to the east within another Petitcodiac tributary- the Little River watershed.

The Maritimes have had human inhabitants for the last 11,000 years (Wicken 2002), though for most of that time precise cultural identities are impossible to determine today. By the early 1600s, when Europeans arrived, much of the native population of coastal Atlantic Canada shared a common culture and language identifying themselves as the L’nuk, “the People”, and recognized by Europeans as the Mi’kmaq. During this time, the Mi’kmaq lived in large villages along the coasts from April to November. They grew corn in small garden plots but were mostly dependent upon fish and game for nourishment. Therefore, they tended not to stay in one place for long given the need to follow their food sources so dispersed inland during the winter to hunt moose and caribou (Wicken 2002).

Table 1: Brief historical background summary for communities along or near the Pollett River

Estimates of the pre-contact population vary between 15,000 to 35,000 in what is now Nova Scotia and New Brunswick (Miller 1976, Marble 1993). This declined between 75% to 90% due to social disruption and epidemics brought by Europeans (such as smallpox) during the first century of contact. By 1616, Jesuit priest Pierre Biard estimated the population as 3,500 (Mooney 1928). Physical impacts on the watershed were few compared to what was to follow.

The Mi’kmaq name for the Pollett River was Manoosaak’ (Provincial Archives of New Brunswick, 2023), The English name for the river is reportedly a reference to Peter Paulet, a Mi’kmaq elder who lived near the mouth of the river (Hamilton, 1996), whose name suggests some degree of Acadian cultural influence. Presumably he was a member of the historical Mi’kmaq community that existed on the north side of the Petitcodiac River between the mouths of the Little & Pollett Rivers.

Ganong’s (1905) map of known First Nations villages and campsites includes this site at Salisbury located along the north bank of main stem of the Petitcodiac, near the head of tide between the mouths of Little River and the Pollett River. A native leaving Beaumont (where there was another camp in the lower Petitcodiac estuary) could ride the 13 km per hour tidal bore upstream to Salisbury, greatly facilitating such travel (Petitcodiac Heritage River Committee 2000). The importance of the Salisbury encampment was due to its location both at the head of tide and near the ends of a pair of portage routes leading to the Saint John River system. The more highly traveled of the two routes crossed from the main stem of the Petitcodiac River to the Canaan River (Ganong 1914) near what is now the Village of Petitcodiac, as doing so provided the best access to the upper St. John and on to the St. Lawrence (Petitcodiac Heritage River Committee 2000). The other route crossed from a tributary of the Petitcodiac, the Anagance River, to the Kennebecasis River (and from there to the lower portion of the Saint John River system). In fact the name Anagance comes from Maliseet “Oo-ne- guncé” meaning portage (Ganong 1896), presumably a reference to the link provided by that tributary.

In the 1630’s the French began to make a serious effort to colonize Atlantic Canada, beginning to arrive in numbers significant enough to develop an enduring Acadian identity (Laxer 2006), at a fairly similar timeframe to the English colonies further south. By 1676 the first Acadian settlers arrived at Beaubassin, near the current Nova Scotia Visitor’s Centre along the Trans-Canada Highway at the New Brunswick border (Larracey 1985). During this time there was much Acadian and Mi’kmaq intermarriage (Marshall 2011) weaving a complex web of family relationships. French authorities encouraged intermarriage to produce a colonial hybrid population, while further south the English tended to aggressively enforce racial segregation (Prins 1996). Meanwhile the Mi’kmaq had begun to adopt Catholicism from the French, while the British were Protestants, at a time when such differences added fuel to conflicts. Acadians also maintained good relations with the Mi’kmaq in part because the lands Acadians occupied either complemented native use, as with fur traders, or were in areas that were marginal to native concerns as in the case of the Acadian farmers on the tidal flats (Mancke 2005).

By 1710, Acadians and Mi’kmaq in peninsular Nova Scotia fell under British control, which was subsequently formalized in 1713 under the Treaty of Utrecht. Previous to the treaty, the French had claimed that the borders of Acadia reached all the way to the Kennebec River (well within in what is now Maine). After the treaty however French Authorities claimed that Acadia was just Port Royal (renamed Annapolis Royal by the British after they seized it in 1710) and the peninsula (modern Nova Scotia excluding Cape Breton). Based on that assertion, the French continued to occupy the mainland (now New Brunswick), in addition to the territory they retained officially under the treaty (Martin 1995) i.e.: Île Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island), and Île Royale (Cape Breton Island). The British were not in a position to contest this reality due to a lack of soldiers and settlers (Ganong 1901). By 1730 the Acadian community in the Petitcodiac was thriving precisely because they were under the jurisdiction of neither Great Brittan nor France (Faragher 2005). That situation did not last, however. With no agreed boundary between English and French territory provided by the Treaty of Utrecht, the French eventually adopted and defended the Missaquash River as the de facto boundary between the two powers (Milner 1911), the same boundary that is in modern use between New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. To Europeans the treaty had merely changed the status of Nova Scotia from a fairly uninhabited French territory with disputed boundaries, to a fairly uninhabited British territory with disputed boundaries (Martin 1995). It was rather more personal to the Mi’kmaq and Acadians who lived there.

Meanwhile, after 1713, New England fisherman pushed more aggressively into Nova Scotia’s coastal waters sparking conflict with the Mi’kmaq (Wicken 2002). By 1726 the Mi’kmaq and the British signed the first of a series of Peace and Friendship treaties. What the British wanted from the agreement was native recognition of the Treaty of Utrecht whereby natives agreed not to molest His Majesty’s subjects in “lawfully” made settlements, and the Crown could regulate the movement of European nationals into Acadia – i.e., exclude the French. In exchange the British agreed not to interfere with native hunting, fishing, planting activities.

In June 1749 Edward Cornwallis established Halifax with 2,500 settlers as a new capital for Nova Scotia (Beck 1979) and constructed the citadel there as a fortress to defend it. This marked the beginning of meaningful efforts by the British to settle the Maritimes. Prior to this time British authority at Annapolis Royal “had been no more than a mock government” that “did not extend beyond the cannon reach of the fort” (Philipps 1720). The Mi’kmaq immediately recognized the implications of this change and reacted with outrage to what they regarded as establishment of an unlawful settlement in violation of the Treaty of 1726, and theft of their land. No responsible indigenous leader could ignore the reality that environmental change brought about by such agricultural settlement was the most lethal threat that British imperial expansion posed to the existing economy, livelihood, and health of the Mi’kmaq (Reid 2013). Violence escalated until by late 1749 Governor Cornwallis proclaimed a policy aimed at “extirpation” of the Mi’kmaq (Paul 2000).

In 1751 the French built Fort Beausejour at the border to protect Acadian communities in what is now New Brunswick from attack by the British. By this time the Acadian population near the Fort had grown to 1,541 people, with an estimated additional 1,100 spread out at Shepody and along the Petitcodiac and Memramcook Rivers (Larracey 1985). The Acadians built dykes and tidal control structures turning marshland along the lower Petitcodiac estuary into pasture, and established their settlements nearby (Wright 1955). Their physical impacts on the Pollett River, what for them was a remote hinterland, were limited.

In 1752 the British signed yet another treaty with the Mi’kmaq reaffirming the 1726 treaty and also modifying it to formalize a commercial relationship between the British and the Mi’kmaq (Wicken 2002), encouraging not only hunting and fishing, but ensuring “free liberty” to sell the products of such activities in Halifax or any other settlement. For the British this provision was critical as an attempt to wean the Mi’kmaq from their friendly relationships with the Acadians and French officials in Louisburg. This treaty subsequently formed the basis of the 1999 Supreme Court Marshall decision and subsequent ongoing modern lobster fishery disputes.

Ganong (1899) notes that like First Nations, the French made use of the Kennebecasis- Petitcodiac portage along the Anagance in order to maintain communication between Fort Beausejour and Acadian settlements on the lower St. John. However the French route between the Canaan and the Petitcodiac to access the upper St. John was slightly different than the one favoured by First Nations, reportedly crossing overland to the Canaan from the North River, rather than the main stem of the Petitcodiac (Raymond 1891). From there messengers from Fort Beausejour, and the Fortress of Louisbourg passed up along the St John to reach Quebec.

After the fall of Fort Beausejour in 1755, the British attempted to expel the Acadians, to open up land for English settlers. There is a record of an Acadian settlement, Village Victuare, located nearby in Salisbury, close to the Mi’kmaq encampment there (Ganong 1930). It was documented in 1758 by British Major George Scott as he was forcefully removing Acadian families from the upper Petitcodiac (Scott 1758). The village appears to have been composed of approximately 10 homesteads, settled in about 1751, and was reportedly the largest Acadian village along the Petitcodiac upstream of Beausoleil Village, modern day Allison. Ganong (1930) suggests that it is likely that in the wake of the expulsion, Acadians briefly occupied locations such as Fourche-à-crapaud at the mouth of Turtle Creek, and on the Coverdale (Little), and Pollett Rivers in order to be near the head of tide and thus above the reach of English Ships. Major Scott apparently found the tidal bore on the Petitcodiac problematic during his raids in 1758, nearly losing two ships on one occasion (Pincombe and Larracey 1990).

The Mi’kmaq sided with the French (Wicken 2002), participating in the defense of Fort Beausejour, as well as the short guerilla war which followed its capture (Grenier 2008). There were several reasons that Mi’kmaq in New Brunswick did so. In addition to intermarriage, prior to the arrival of the British, native communities had already established trade networks with the Acadians for steel tools, weapons and other European goods (Walls 2010). Another source of friction was that the Mi’kmaq had begun to adopt Catholicism from the French, while the British were Protestants, at a time when such differences added fuel to conflicts. Acadians also had had good relations with the Mi’kmaq in part because the lands Acadians occupied either complemented native use, as with fur traders, or were in areas that were marginal to native concerns as in the case of the Acadian farmers on the tidal flats (Mancke 2005). English settlers on the other hand tended to seize land the Mi’kmaq valued, to clear the forest for agriculture (Francis et al. 2010).

Throughout 1760 and 1761 the British also signed a series of Peace and Friendship treaties with individual native communities, reaffirming the treaties of 1726 and 1752 (Wicken 2002), with the signature at Chignecto/ Missaquash occurring on July 8th, 1761. The important distinction with this iteration of the treaties was the provision by which natives agreed not to trade with the French. To ensure that such trade did not occur the British agreed to establish “truck houses” as points of trade near native communities.

The Treaty of Paris in 1763 ended the Seven Years War, with France ceding its territory in Canada and the Maritime region to Britain, except for the small islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon in the Gulf of St. Lawrence (Ganong 1901; Faragher 2005). The latter France retained in the interest of preserving its access the lucrative fishery in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the Grand Banks (MacNutt 1970). Shortly there after a royal proclamation set the boundary between Canada (Québec) and Nova Scotia as being the watershed between the Saint Lawrence and points south until reaching the north coast of the Bay of Chaleur. All of Nova Scotia north of the Bay of Fundy (modern New Brunswick) was made part of Cumberland County. In 1765 that was changed to make the Saint John River into Sunbury County. There was no formally defined boundary between Sunbury and Cumberland Counties until 1770 when it was set as a somewhat arbitrary line beginning at Mispec (a short distance along the coast east of the mouth of the Saint John River) headed due north to the Canadian (Québec) border (Ganong 1901).

With peace, in 1763, Acadians throughout the region became British subjects, but this was not the case for First Nations, whose situation was more complex (Beaulieu 2014). The British defeat of France at Louisburg in 1758 encouraged the political collapse of the Mi’kmaq population in Nova Scotia as a fighting force as the peace and friendship treaties signed between 1760 and 1761 brought an end to Indigenous-French relations and alliances (Patterson 1993). Between typhus brought by the d’Anvill expedition, violence promoted by LeLoutre, and Cornwallis’ policy of Mi’kmaq extirpation, by 1763 First Nations had been decimated by decades of warfare and disease, with some estimates suggesting that there may have been fewer than 500 individuals remaining in the Maritimes (Statistics Canada 2020).

In 1764 the British government began to allow Acadians to resettle in Nova Scotia with the provision that they remain in small groups scattered throughout the province (MacNutt 1963). Initially they were not allowed to settle in groups larger than 10 persons, the goal being to keep them at great distances from each other, or even ultimately discourage them from remaining in the colony at all. Since the authorities did not give those Acadians who remained a fully legal position by making grants of land, their status was little better than squatters (MacNutt 1963). It is an important and sobering reminder that eighteenth-century people understood that military disruptions did not have the long-term permanence that they might want, without civil validation (Mancke 2019). Consequently, the ultimate dispossession of Acadians came not through the barrel of a gun, but through the power of the pen, and less in the heat of war, than in the quiet of peace.

During the American Revolution, control of Fort Cumberland (formerly Fort Beausejour) was briefly contested by rebels in 1776. Though unsuccessful, the participation of Mi’kmaq and Maliseet in the siege highlighted the vulnerability of Nova Scotia and prompted the Crown to enter into what became the final round of Maritime Peace and Friendship Treaties with First Nations in 1778 and 1779, reaffirming the previous treaties (Patterson 2009).

The Revolutionary War ended with yet another Treaty of Paris, this one in 1783 (MacNutt 1963, Ganong 1901). Early in the war the Americans had taken it for granted that winning their independence also implied the acquisition of the two provinces (Nova Scotia and Canada) that had not revolted. In the end however, the agreed terms established rough boundaries between British holdings and the newly recognized United States, that while not yet finalized along the St. Croix River, were distant from the Pollett River. The peace fell short of the hopes and expectations both sides had harbored during the war, but despite the distance from the border, was not without implications for the Pollett. For every Loyalist within British lines, there were five left living within territories dominated by the Continental Congress (MacNutt 1963). To such Loyalists, peace and recognition of the United States meant surrender of themselves and their possessions to those that had been their enemies. Although the Treaty of Paris promised Loyalists a safe return to their pre-war homes, persecution of “Tories” escalated with the rebel victory (Dallison 2003). An attractive and safer alternative became clear. Across the water lay Nova Scotia, a (comparatively) vacant land which remained beneath the British Crown (MacNutt 1963).

As things warmed in the spring of 1783 the movement began, with all parts of the coastline receiving refugees, many of which landed on the north shore of the Bay of Fundy (Squires 2000), of which approximately 11,000 eventually stayed on (Wynn 1981a), tripling the population from a little more than 5,000 to more than 16,000 in less than a year. Almost 10% of the refugees were black loyalists, and 10% of those (i.e., approximately 1% of total Loyalist refugees) arrived in the region as slaves. (Hodges 1996). The main point of penetration was the Saint John River Valley, however, the Petitcodiac, Memramcook, and Chignecto regions each received a share Loyalist refugees as well (Wright 1945, Milner 1967, Bowser 1986).

Even before departure from New York, Loyalists had begun to contemplate a separate and distinct province (Dallison 2003), and support for the concept only grew once they arrived in Nova Scotia. Governor Parr began escheating parts of pre-Revolution grants immediately to provide lands for the newcomers jamming into port towns clamouring for land (Fellows 1971). The need for land was paramount as it meant survival, food, and fuel- as well as status and wealth. Parr’s inability to release land quickly enough frustrated Loyalists (Snowdon 1983) and was a key factor driving calls for partition (Gilroy 1933). Edward Winslow, an individual responsible for settling Loyalist Regiments in Nova Scotia became a leading proponent for partition arguing in a letter to his friend Ward Chipman in 1783, “Take the general map of this province (even as it is now bounded) observe how detached this part is from the rest, how vastly extensive it is, notice the rivers, harbours, etc. Consider the numberless inconveniences that must arise from its remoteness from the metropolis and the difficulty in communication. Think what multitudes have and will come here, and then judge whether it must not from the nature of things immediately become a separate government” (Winslow 1783).

Halifax was opposed to Nova Scotia being subdivided for obvious reasons (Chipman 1784), however the authorities in London agreed (Gilroy 1933). On June 18th, 1784, Nova Scotia was partitioned, and the north shore of the Bay of Fundy became New Brunswick, a self governing “Loyalist” province. Once again the Missaquash River was selected as the boundary (Allison 1916), with the Pollett watershed falling within what became Westmorland County (Ganong 1901). Thomas Carleton arrived in November 1784 to establish the new government and direct the colonization of New Brunswick (Fellows 1971). With access to title to land having been a driving factor in its formation, the newly established Province of New Brunswick required that existing land grants be re-registered both to facilitate escheat and to establish clear title for active landowners (Kernaghan 1981), and the House of Assembly focused on allocation of land as one of its initial priorities (Fellows 1971).

The dates that various communities listed in Table 1 were first settled (where available) indicate how movement by English colonists into the upper reaches of the Petitcodiac River above the head of tide occurred first along the more easily accessible main stem. Many of the early dates coincide with the arrival of United Empire loyalists from the 13 colonies (late 1770’s – 1780’s). After the arrival of the Loyalists, Mi’kmaq in what is now New Brunswick were moved off their lands and onto “reserves” (Walls 2010). This was done partially to provide land to incoming settlers, and partially to punish the Mi’kmaq for aligning themselves with the French.

Subsequent generations of English settler families and those that arrived after them then pushed further up the Petitcodiac and into its more remote tributaries such as the Little River, and the Pollett River (Wright 1945). An early example would be John Colpitts, the eldest son of Robert Colpitts who had settled near Salisbury in 1783. John Colpitts arrived from England as a teenager with his father, and had already moved on to develop his own homestead just a few years later, founding Colpitts Settlement on the Little River (Moncton Daily Times, Thursday August 26th 1920).