Third Level Assessment – Aquatic and Riparian Habitat Assessment

Wildlife

Several species of wildlife warranting specific attention occur in the Little River watershed: iBoF Atlantic salmon(Salmo salar), Brook Floaters (Alasmidonta varicosa), American eels (Anguilla rostrata), and wood turtles (Glyptemys insculpta).

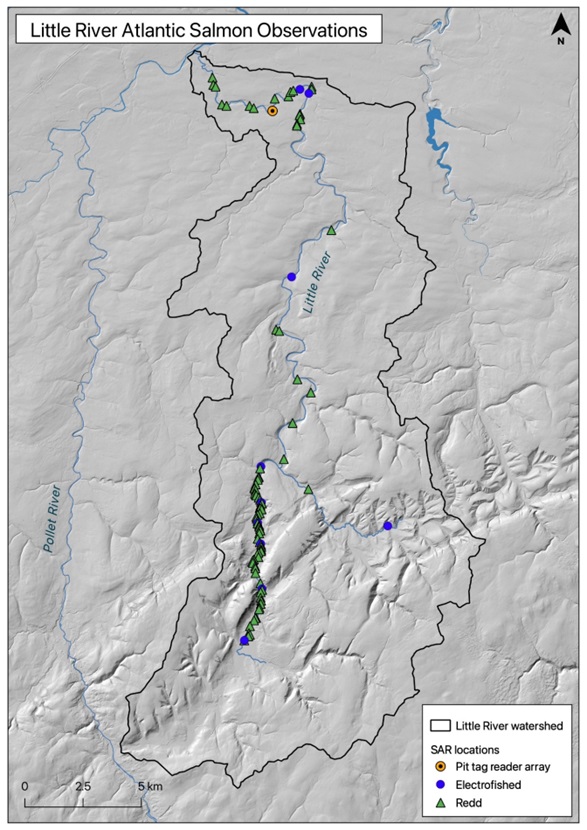

Inner Bay of Fundy (iBoF) Atlantic salmon populations were listed as endangered under the Species at Risk Act in 2003 (DFO, 2010; SARA Registry, 2013a). Salmon are considered extirpated from the Petitcodiac, except for those introduced in stocking programs (AMEC 2005). Observations of Atlantic salmon are plotted in Figure 8.

American eels were designated as “Special Concern” by COSEWIC in 2006 (COSEWIC 2006). Their status was re-examined and raised to “Threatened” in 2012 (COSEWIC 2014a). This species is being considered for listing under the Federal Species at Risk Act, but currently it has no status (SARA Registry 2013b).

Wood turtles were designated as “Special Concern” by COSEWIC in 1996 which was raised to “Threatened” in 2007 (COSEWIC 2007; COSEWIC 2011). This species is listed as “threatened” under the Species at Risk Act (SARA Registry, 2012).

Brook Floaters are a medium sized species of freshwater mussel listed as Special Concern by COSEWIC (COSEWIC 2009), and as Schedule 1, Special Concern, under the Species at Risk Act (SARA) in 2013 (DFO 2016).

Guidelines for restoration projects in areas with these species are in Appendix. Unlike the Pollett, striped bass have not been documented in the Little River, but given their presence on the Pollett, likely venture into the mouth of the Little River and possibly as far upstream as the Rt. 112 bridge. Striped bass in the Bay of Fundy were designated “Endangered” by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) in 2012 (COSEWIC 2014b) and are being considered for listing under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA), but currently have no status (SARA Registry 2018).

The modern decline in iBoF salmon within the Petitcodiac is a marked contrast to the abundance described by early settlers. Construction of the Moncton to Riverview causeway in 1968 eliminated fish passage for adult salmon and smolts and effectively (but for ongoing intervention) extirpated the species from a river system that represented 20% of the total iBoF population (Locke, et al. 2003). That said numbers of this species had been decreasing for decades due to the impacts of other human activities (Elson 1962), long prior to construction of the causeway.

Survival and development of salmon fry released along the Little River since the causeway gates were opened in 2010 have been monitored by annual electrofishing at the release sites and occasional use of fyke nets and a counting fence. In recent years, adult salmon have been released into the river- as non-targeted fish from DFO’s Live Gene Bank at Mactaquac. Unlike the Pollett River, the Little River does not receive Fundy Salmon Recovery (FSR) adults grown to maturity in sea cages in Grand Manan. The purpose of adult releases is to repopulate the river with their progeny. These offspring will have undergone natural selection for conditions within the Petitcodiac, and will recognize its headwaters as their natal streams, preferentially returning to it to spawn (rather than the Big Salmon River- the origin of the DFO Live Gene Bank fish).

Large numbers of salmon redds detected in the upper Little shown in Figure 8 show that significant spawning takes place following these stocking efforts. Electrofishing of release sites and the counting fence have detected numerous fry, parr, and smolt indicating that the spawning has been successful and survival of juveniles has been good. Numerous smolt have subsequently been incorporated into the FSR program and sent to the Sea cages at Grand Manan. In the late summer and fall of 2021 four PIT tagged salmon were detected returning to the Little River by an automated PIT tag reader antenna array FFHR operates located at the first Rt. 895 bridge. Of these salmon, three were FSR Little River origin fish, having been collected by the counting fence near that bridge in the spring of 2019 as smolts, raised to adulthood in Grand Manan and released on the Pollett River (where all FSR fish are released) in the fall of 2020. Yet in 2021, when these Little River salmon returned to spawn yet again, they did so preferentially to their natal river, the Little River. Subsequently, in 2022 electrofishing found fry in that part of the Little River (where no fry or adults had been released) suggesting that successful spawning took place nearby in the lower Little during the fall of 2021.

Completion of the new bridge between Moncton and Riverview in 2021 to partially replace the Petitcodiac Causeway has strongly advanced iBoF Atlantic salmon recovery efforts in the Petitcodiac. That fall, the first wild returning adult was captured upstream of the mouth of the Little River, along the main stem of the Petitcodiac at the head-of-tide in Salisbury on October 4th. She lacked both a PIT tag and a floy tag. She showed no scars from having shed either type of tag, nor did it look as though a tissue sample had been taken from her caudal fin. In short, there was no sign that she had been previously handled- so scale and tissue samples were taken to allow further investigation. Stable Isotope Analysis carried out by the Stable Isotopes in Nature Laboratory (SINLAB) at the University of New Brunswick (UNB) confirmed that she was a returning wild iBoF Atlantic salmon (Samways personal communication 2021; Redfield 2022), never handled by FFHR prior to her capture. Having been captured on the main stem of the Petitcodiac beyond the mouth of the Little River, it seems reasonable to speculate that she was on her way upstream back to the Pollett River, the other Petitcodiac tributary that offers significant spawning habitat.

She is probably not alone – the FNT merely samples what is in the river. Catching one indicates that numbers have reached a level where the trap can detect them. It is premature to attribute detection of the wild salmon in 2021 entirely to the new channel under the bridge. That said however, she must have passed under the bridge, and the improved passage can only have helped her to return. No additional returning wild adults were caught during the following year. The lack of such fish in 2022 was noteworthy, and though somewhat disappointing, not particularly surprising. It does not mean that the individual caught in 2021 was a fluke, but merely highlights the fact that catching the first wild return was an unusual event. Two things can be simultaneously true: i.e. that the odds of catching such a fish have increased as a result of ongoing iBoF Atlantic salmon recovery efforts, and that yet such fish are still uncommon enough that doing so remains unlikely.

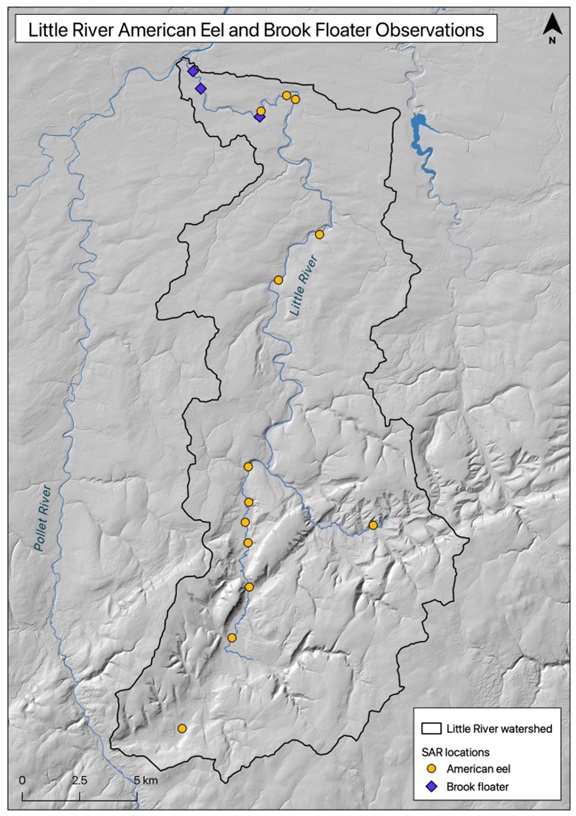

Brook Floaters (cover, bottom photo) have been found in the lower reaches of the Little River from the mouth up to the Rt. 895 Bridge near Synton (Figure 9). During the surveys DFO conducted in the late 1990s this portion of the river was home to the best sites with the most abundant populations of Brook Floaters within the entire Petitcodiac Watershed (Hanson and Locke 2001). Twenty years later, when FFHR revisited these sites in 2018 only a few of those at which Hanson and Locke (2001) detected brook floaters retained their original abundance. The biggest change occurred on the Little River above the Rt 112 Bridge. That site had had the greatest population in 1997-98, rated as common (Hanson and Locke 2001), suggesting that this site supported a density somewhere between 0.1 and 1 brook floaters per m2 at that time. Hanson’s communication with the authors of the 2009 COSEWIC Assessment indicated that would have been consistent with the presence of certainly hundreds, possibly thousands of brook floaters. FFHR’s 2018 surveys found 5 brook floaters there. When contacted for his insights, Hanson (Personal Communication 2018) confirmed that just as extrapolating the reported density in 1997-98 to the area surveyed suggested, this site had supported hundreds of brook floaters when they surveyed it- so many in fact, that it had not been practical to count them individually.

In addition to being a DFO scientist, Hanson is an angler, and regularly fishes the Little River recreationally. He indicated that one challenge with brook floaters is that their specific habitat needs tend to make them occur in clumps. Specifically in the area above the 112 bridge on the Little River, the persistent sand and gravel bar there was home in 1997-98 to literally hundreds of brook floaters. In either 2011 or 2012, this entire bar (plus the rest of the area), was completely covered by a thick mat of algae (15 cm or more). These thick mats of green algae extended over most of the lower 4 or 5 km of the Little River. If one moved the algae, hydrogen sulfide and methane erupted in amounts sufficient to make one gag. Every freshwater mussel was killed in that part of the Little River, including the brook floater bed at this site above the 112 Bridge. A short distance below the mouth of the Little River, on the main stem of the Petitcodiac, Fort Folly Habitat Recovery was operating its fish trap downstream on the main stem of the Petitcodiac at the same time in both 2011 and 2012, and extreme quantities of algae were observed there as well, creating operational challenges by fouling the net.

Hanson (Personal Communication 2018) indicated that for the next three or four years, there were no brook floaters in this area. He found zero mussels of any species at that site in 2013, when looking on behalf of the DFO SARA office. He has only seen a few to perhaps a dozen during each of the last several years at this site. There has been some recolonization by eastern floater (in backwaters) and some pearl mussels washed downstream during spring and fall freshets – but nothing like the numbers that used to be present. There are still a lot of nutrients washing into the river both as manure (turning the water dark grey and cloudy with a very strong manure smell) and pelleted lawn fertilizer. He reports standing in the river and being pelted by a shower of lawn fertilizer at least once every fishing season. The algae growth, however, has never again approached the state observed in 2011 or 2012. Another very clear difference he has observed now compared to 20 years ago is that fine grey or black silt is almost always present over what had been gravel / cobble / boulder habitat and that he has noticed a decrease in numbers of mayflies, caddisflies and stoneflies from the 895 bridge down to the head of tide.

American eels were encountered at numerous sites (Figure 9) the full length of the Little River. Eels have been seen while electrofishing, in the counting fence just below the 895 bridge, and in the case of The Ducks Unlimited Canada (DUC) empondment at the very top of the Little – in eel pots. In the decades that the causeway gates were closed downstream on the Petitcodiac, eels had more success than salmon or striped bass navigating the fishway and accessing the upper reaches of the river, such as the Pollett. Aside from that, being catadromous, instead of anadromous like salmon, the eel population was less vulnerable to extirpation as they are not dependent upon consistently accessing a river to perpetuate future generations within that river. Instead, their spawning takes place in the Sargasso Sea, and young eels arrive at and reside in different rivers than those in which their parents had lived (COSEWIC, 2006). This allowed for a steady stream of incoming eels, despite the causeway, arriving to colonize the river anew each generation. The fact they are found at the very top of the Little in the DUC empondment indicates that they can be assumed to be at least periodically present at any location downstream of that point. This suggests that eels have access to the entire watershed, which is not surprising given the ability of this species to spend extended periods of time out of water while navigating overland around barriers (Van Den Avyle 1984), as well as the ability of juveniles to climb damp vertical surfaces.

Wood Turtles have frequently been encountered within the Little while conducting field work, is more a reflection of where FFHR does field work in the river than the result of years of surveys on the scale that yielded locations for salmon, striped bass, and eels. That said, from 2014 to 2016 the Petitcodiac Watershed Alliance (PWA) carried out Wood Turtle surveys across the Petitcodiac watershed, and in the process documented numerous Wood Turtles within the Little River. Due to their small home range, and vulnerability to poaching, encounters with wood turtles are considered to be sensitive information, and so are being withheld here. Wood turtles are terrestrial turtles that require forest cover, clean water courses, and access to gravel or sand for nesting. Disturbance caused by failing riverbanks appears to create gravel bar habitat favorable to Wood Turtles, prompting concern about impacts of bank stabilization projects on Wood Turtles in nearby habitat.