Third Level Assessment – Aquatic and Riparian Habitat Assessment

Geomorphic Assessments

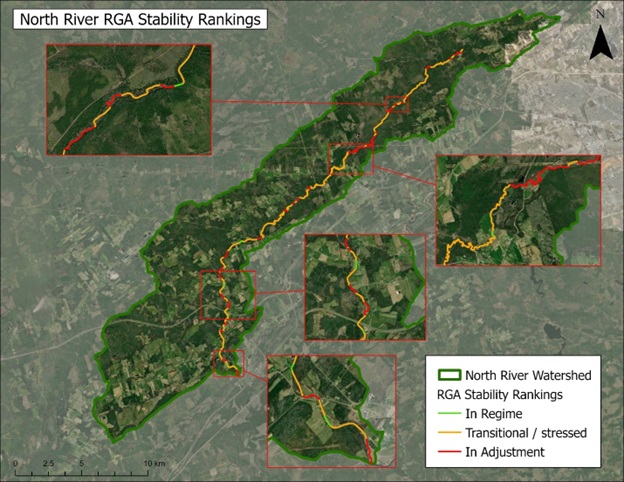

Data collected from the Rapid Geomorphic Assessment (RGA) was used to evaluate the geomorphic condition and stability of the assessed reaches North River. In order to interpret the geomorphic data, the included maps of the watercourse are highlighted according to reach stability as well as the Primary Geomorphic Processes impacting each reach.

Rapid Geomorphic Assessments are used to quantify channel stability based on the presence and (or) absence of key indicators of channel adjustment with respect to four categories: 1) Aggradation, 2) Degradation, 3) Channel Widening, and 4) Planimetric Form Adjustment. Each indicator is described in detail below.

Aggradation

Channel aggradation may occur when the sediment load to a river increases (due to natural processes or human activities), and it lacks the capacity to carry it. Piles of sediment in the river can re-direct flows against the banks, leading to erosion and channel widening.

Typical indicators used to identify aggradation include:

- Shallow pool depths.

- Abundant sediment deposition on point bars.

- Extensive sediment deposition around obstructions, channel constrictions, at upstream ends of tight meander bends, and in the overbank zone.

- Most of the channel bed is exposed during typical low flow periods.

- High frequency of debris jams.

- Coarse gravels, cobbles, and boulders may be embedded with sand/silt and fine gravel.

- Soft, unconsolidated bed.

- Mid-channel and lateral bars.

Degradation

Degradation occurs as the river cuts deeper into the land and decreases its gradient. This can occur from a rapid removal of streambed material due to an increase in discharge, water velocity, or a decrease in sediment supply. Bed lowering can move in both an upstream (as a headcut or nick point) and/or downstream direction.

Indicators of degradation include:

- Elevated tree roots.

- Bank height increases as you move downstream.

- Absence of depositional features such as bars.

- Head cutting of the channel bed.

- Cut face on bar forms.

- Channel worn into undisturbed overburden/bedrock.

Widening

Widening typically follows or occurs in conjunction with aggradation or degradation. With aggradation, banks collapse when flows are forced on the outside, and the river starts to widen. Wide, shallow watercourses have a lower capacity to transport sediment and flows continue to concentrate towards the banks. Widening can be seen with degradation, as it occurs with an increase in flows or decrease in sediment supply. Widening occurs because the stream bottom materials become more resistant to erosion (harder to move) by flowing waters than the stream banks.

Indicators of widening include:

- Active undermining of bank vegetation on both sides of the channel, and many unstable bank overhangs that have little vegetation holding soils together.

- Erosion on both right and left banks in riffle sections.

- Recently exposed tree roots.

- Fracture lines at the top of banks that appear as cracks parallel to the river, which is evidence of landslides and mass failures.

- Deposition on mid-channel bars and shoals.

- Urbanization and storm water outfalls leading to higher rate and duration of runoff and channel enlargement typically in small watersheds with >10% impervious surface.

Planform Adjustment

These are the changes that can be seen from the air when looking down at the river. The river’s pattern has changed. This can happen because of channel management activities (such as straightening the bends of the river with heavy equipment). Planform changes also occur during floods. When there is no streambank vegetation with roots to hold soil in place, rivers cut new channels in the weak part of the bank during high water. Planform adjustments typically are responses to aggradation, degradation, or widening geomorphic phases.

Indicators of Planform Adjustment include:

- Flood chutes, which are longitudinal depressions where the stream has straightened and cut a more direct route usually across the inside of a meander bend.

- Channel avulsions, where the stream has suddenly abandoned a previous channel.

- Change or loss in bed form, sometimes resulting in a mix of plane bed and pool-riffle forms.

- Island formation and/or multiple channels.

- Additional large deposition and scour features in the channel length typically occupied by a single riffle/pool sequence (may result from the lateral extension of meanders).

- Thalweg not lined up with planform. In meandering streams, the thalweg typically travels from the outside of a meander bend to the outside of the next meander bend.

- During planform adjustments, the thalweg may not line up with this pattern.

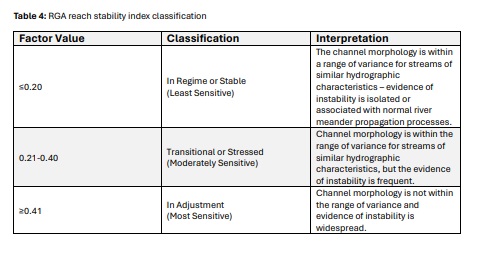

Upon completion of the field inspection, indicators are tallied for each category to produce an overall reach stability index. The index classified the channel in one of three stability classes:

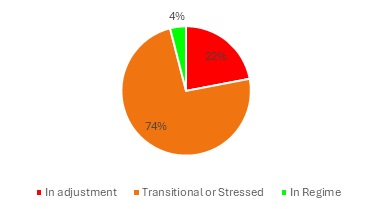

The RGA stability index results for the North River are shown in Figure 9. Approximately 22% of the reaches are in adjustment – as per Table 4- the most sensitive state. Only 4% of the reaches assessed were found to be stable (in regime). The remaining 74% were transitional between these two states.

Primary Geomorphic Processes

The primary geomorphic process identified on the North River are shown in Figure 11. Aggradation was the most common process observed at 47%, followed by Degradation 26%, Widening 26%, and Planiform adjustment 1%,

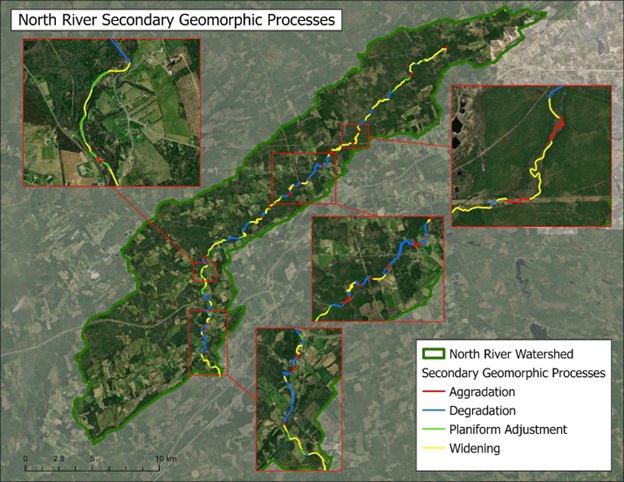

Secondary Geomorphic Processes

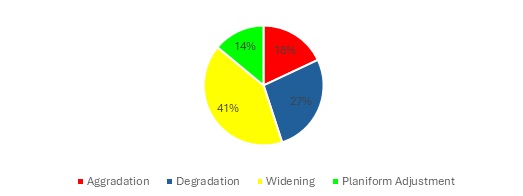

The secondary geomorphic process identified on the North River are shown in Figure 13. Widening was the most common process observed at 41%, followed by Degradation 27%, Aggradation 18%, and Planiform adjustment 14%.

This RGA data indicates that most of the riverbanks along the North River are experiencing some degree of stress and disturbance. Unlike the main stem of the Petitcodiac, where 66% of the channel is “in adjustment”, only 22% of the North River is. Instead, the majority of reaches within the North are “transitional or stressed”. The primary form of this stress due to aggradation, where sediment is piling up in the river and re-directing flows against the banks. That in turn is producing the erosion that is driving widening as the secondary process in the river. Such disturbance is widely distributed throughout the river, rather than being part of a gradient going either upstream or downstream.

The purpose of RGAs is to inform future plans by helping to identify and prioritize areas needing the most attention. The reaches that are “in adjustment” are where from a stability perspective, problems are most acute. That said, “transitional or stressed” reaches may also warrant greater attention considering other factors – such as wildlife, say the brook floaters in Figure 8 just above the Glenvale bridge a short distance upstream of the Village of Petitcodiac. Landowner interest is another significant consideration, as will be explored in more detail as part of the process of developing the Aquatic Habitat Rehabilitation Plan.